A host of mall management companies are eyeing a Rs 24,000-crore market

When Noaman and Irfan Razack began developing commercial properties in the early 1980s in Bangalore, they realised that most land owners did not have the skills to run the malls once they were built. Often, a developer only knew the basics — collecting common area maintenance charges and administering the security — without paying any attention to consumer and tenant-retention skills. “We decided to build this skill into our business. Now, every large developer offers this service,” says Noaman Razack, director of the Rs 1,000-crore Prestige Group in Bangalore. Four malls and a decade later, mall management is becoming a profit centre for the real estate company.

Large malls such as Mumbai’s Phoenix Mills and Inorbit and Bangalore’s Mantri Square (500,000-1.5 million sq. ft in size and with average annual revenue of Rs 1,000 crore) are creating the blue print for mall operations in India. The Mantri Group, for example, has set up a subsidiary, PropCare, for precisely this purpose.

In 2011, when the Royal Meenakshi Mall was built in Bangalore, PropCare took over as its sole manager. “The mall was built by someone else, but we won the mandate to run it for the developer,” says Jonathan Yach, CEO of PropCare and Mantri Square. This new business has branched off into branding the mall and building customer relationships, too. Mall managers not only undertake maintenance and security, but also run promotions within the mall to drive traffic into the stores — a boon for retailers.

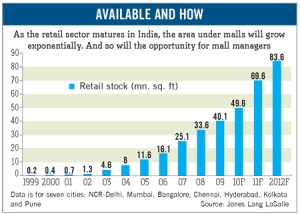

Though only a few companies see mall management as a separate entity at present, it is only a matter of time before the business booms. The total number of malls across India has gone up to 240 in 2010 from just 20 in 2003, translating into 120 million sq. ft of retail space. Though only 30 of these malls are run by mall management companies, the number is expected to shoot up as organised retail matures.

According to real estate consultancy Jones Lang LaSalle (JLL), it is a Rs 24,000-crore business opportunity, which will double in the next 10 years. Small wonder then that JLL along with other consultant companies such as Knight Frank and CB Richard Ellis are pitching for this business.

Among the bigger players to have recognised the opportunity are Prestige Group, PropCare, Phoenix and Central (see ‘Sharp Aim’). In fact, Future Group’s Central was among the first to explore the concept of keeping the owner of the property and the developer in the background and letting the retailers run the mall. “Our business model works as a shop-in-shop for brands. Central is a seamless retail space,” says Sandeep Mukim, the chief of operations at Central and Brand Factory. Central, which currently manages 16 malls, monitors the operations and tracks conversions for its tenants; security and maintenance are outsourced. “Central as a brand is all about property management,” says Mukim. The Future Group plans to open 24 Central malls in the next two years.

“The scope of mall management services has now been elevated to shopping centre management. But very few companies have upgraded their capabilities,” says Ashutosh Beri, managing director of property and asset management at JLL. He says clients now expect complete shopping centre management — a drastic shift from the past. According to JLL, the Indian psyche is skewed towards self-sufficiency and most mall owners saw mall management as a simple function of managing facilities. But with increase in competition, more developers have started outsourcing the overall management of their malls to professional agencies. And this trend is likely to catch on as the battle for footfalls gets tougher.

An Evolving Field

The business model for a mall management company depends on which state the mall is in. “Scientific models are available by which common area maintenance (CAM) charges can be predicted with a fair degree of accuracy prior to the launch of a mall,” says Beri of JLL. CAM is dependent on energy costs (both state-supplied and captive energy sources) and also on minimum wages, which again vary from one state to the other. Another factor is the architecture of plants and equipment, which should be in consonance with the usage pattern of the mall.break-page-break

A mall management company makes money on the collections on behalf of the developer. So, say, the mall management company collects 98 per cent of the total cost (including water, electricity, rent and other CAM costs such as security and cleaning), it will be paid 3 per cent on the collections as fee. This may seem high but the job is tough. Mall managers not only spend a considerable amount of time chasing payments from retailers and choosing the right anchor tenants to increase footfalls in the mall, but they also have to spend a lot on promotions.

“Every property that you manage is different because of the catchment and the kind of promotions that you run with it,” says Rajendra Kalkar, the centre director for Phoenix Mills, which plans to open malls in four more cities by the end of the next financial year. A mall manager has to run the business based on what retailers and customers want. Take, for example, luxury malls. The challenge for a mall management company is to provide synergy to competing compatible brands targeting affluent buyers. It must provide a unique gateway to the luxury marketplace. “Achieving this is a fine art, combining the most evolved concepts of human psychology, aesthetics and marketing strategy,” says Shubhranshu Pani, managing director of retail services at JLL.

At present, however, most mall developers in India continue to run the mall themselves because they feel there aren’t sufficient mall management companies. “It is great for developers to hive off this business in the future. At present, there are not many skilled people who can brand and run malls at the same time,” says Kishore Bhatija, CEO of Inorbit Mall in Mumbai. He adds that since people no longer want to travel long distances to shop, for developers it is a business where one has to understand catchment marketing and then build the mall management business.

“In India, developers control the zoning, leasing, finance and marketing in the mall. In developed markets, even these functions are managed by specialist companies and not developers,” says Nirzar Jain, general manager of Oberoi Mall in Mumbai.

Where Is It Heading

With most mall developers spending approximately Rs 200 crore on 500,000 sq. ft of retail space, advice on running the mall successfully can make all the difference. Some Indian malls are turning to malls abroad and taking regular inputs from them. For example, the Mantri Mall in Bangalore works with a South African mall, Cresta Shopping Centre in Johannesburg, on operations and collections. “There is a need for mall management to pick up as developers will need advice on how organised retailing works,” says Pinakiranjan Mishra, national leader for consumer practice at Ernst & Young.As part of their responsibilities, mall managers are required to determine the correct mix of entertainment, shopping and accommodation that will help diversify the tenant mix and de-risk the developer’s investment. It also allows the developers to better utilise the floor-space index and location.

“Service standards are judged the moment people enter a mall. It is more like hospitality business,” says Yach of PropCare. High service standards help in adding value to retailers and also allows people to shop better, he feels.

The ultimate aim of all such exercises is to generate income for the retailers as well as the developers. Many developers are now giving sharing revenue options to retailers. Several malls that became operational during the slowdown opted for a combination of minimum guarantee and revenue sharing, which ensured floor earnings for the developer. Mall management companies use such data to predict the success of the retailer and collect revenues. With better mall management practices being adopted, steps that will increase transparency in revenue recognition are expected to find more takers. Industry experts add that this will also give developers more confidence to introduce innovative rental sharing arrangements with retailers.“There are still relatively few developers who are comfortable with the idea of not just developing the building, but also operating and nurturing the mall as a retail environment,” says Devangshu Dutta, CEO of Third Eyesight, a retail consultancy in Delhi. He adds that those developers who see this as a 25-30 year business income rather than a capital gains income opportunity will survive.

Developers view their role as limited to looking after things like maintenance, utilities, housekeeping and security, whereas successful shopping centre management companies take full charge of managing the tenant mix and the customer footfall. According to Third Eyesight, of the projects being discussed in early-2005, less than 10 per cent would truly succeed as malls — about a third would get converted into offices or alternative uses, and the balance would never take off.

The proof is in the pudding. Indian real estate developers who have built up retail experience will start pitching for malls that are built by developers who have no experience in retailing. The success of this business will entirely depend on whether the customer returns to a mall regularly, or not.

Maximising Footfalls

24 Saturday Mar 2012

Posted in Uncategorized